It was a bright cold starry night on Lake Chippewa.

Lake Chippewa was a “living” lake then,

though soon afterward it would choke and die.

In the bright cold morning after we could spy

them only through a patch of ice brushed clear of snow.

Scarcely three feet below,

they were oblivious of us.

Together beneath the ice in each other’s arms.

Jean-Marie’s head rested on Troy’s shoulder.

Their hair had floated up and was frozen.

Their eyes were open in the perfect lucidity of death.

Calmly they sat upright. Not a breath!

It was 1967, there were no seat belts

to keep them apart. Beautiful

as mannequins in Slater Brothers’ window.

Faces flawless, not a blemish.

Yet—you could believe

they might be breath-

ing, for some trick

of scintillate light revealed

tiny bubbles in the ice,

and a motion like a smile

in Jean-Marie’s perfect face.

How far Troy’d driven the car onto Lake Chippewa

before the ice creaked, and cracked, and opened

like the parting of giant jaws—at least fifty feet!

This was a feat like his 7-foot-3.8-inch high jump.

In the briny snow you could see the car tracks

along the shore where in summer sand

we’d sprawl and soak up sun

in defiance of skin carcinomas to come. And you could see

how deftly he’d turned the wheel onto the ice

at just the right place.

And on the ice you could see

how he’d made the tires spin and grab

and Jean-Marie clutching his hand Oh oh oh!

The sinking would be silent, and slow.

Eastern edge of Lake Chippewa, shallower

than most of the lake but deep enough at twelve feet

to suck down Mr. Dupuy’s Chevy

so all that was visible from shore

was the gaping ice wound.

And then in the starry night

a drop to -5 degrees Fahrenheit

and ice freezing over the sunken car.

Who would have guessed it, of Lake Chippewa!

Now in the morning through the swept ice

there’s a shocking intimacy just below.

With our mittens we brush away powder snow.

With our boots we kick away ice chunks.

Lie flat and stare through the ice

Seeing Jean-Marie Schuter and Troy Dupuy

as we’d never seen them in life.

Our breaths steam in Sunday-morning light.

It will be something we must live with—

the couple do not care about our astonishment.

Perfect in love, and needing no one to applaud

as they’d been oblivious of our applause

at the Herkimer Junior High prom where they were

crowned Queen and King three years before.

(In Herkimer County, New York, you grew up fast.

The body matured, the brain lagged behind,

like the slowest runner on the track team

we’d applaud with affection mistaken for teen mockery.)

No one wanted to summon help just yet.

It was a dreamy silence above ice as below.

And the ice a shifting hue—silvery, ghost-gray, pale

blue—as the sky shifts overhead

like a frowning parent. What!

Lake Chippewa was where some of us went ice-fishing

with our grandfathers. sometimes, we skated.

Summers there were speedboats, canoes. There’d been

drownings in Lake Chippewa we’d heard

but no one of ours.

Police, fire-truck, ambulance sirens would rend the air.

Strangers would shout at one another.

We’d be ordered back—off the ice of Lake Chippewa

that shone with beauty and onto the littered shore.

By harsh daylight made to see

Mr. Dupuy’s 1963 Chevy

hooked like a great doomed fish.

All that privacy yanked upward pitiless

and streaming icy rivulets!

We knew it was wrong to disturb the frozen lovers

and make of them mere bodies.

Sweet-lethal embrace of Lake Chippewa

But no embrace can survive thawing.

One of us, Gordy Garrison, would write a song,

“Too Young to Marry But Not Too Young to Die”

(echo of Bill Monroe’s “I Traced Her Little Footprints

in the Snow”), which he’d sing with his band the Raiders,

accompanying himself on the Little Martin guitar

he’d bought from his cousin Art Garrison

when Art enlisted in the U.S. Navy and for a while

it was all you’d hear at Herkimer High, where the Raiders

played for Friday-night dances in the gym, but then

we graduated and things changed and nothing more

came of Gordy’s song or of the Raiders.

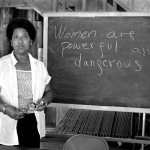

“TOO YOUNG TO MARRY BUT NOT TOO YOUNG TO DIE”

was the headline in the Herkimer Packet.

We scissored out the front-page article, kept it for decades in a

bedroom drawer.

(No one ever moves in Herkimer except

those who move away, and never come back.)

The clipping is yellowed, deeply creased,

and beginning to tear. When some of us stare

at the photos our hearts cease beating—oh, just a beat!

It was something we’d learned to live with—

there’d been no boy desperate to die with any of us.

We’d have accepted, probably—yes.

Deep breath, shuttered eyes—yes, Troy.

Secret kept yellowed and creased in the drawer,

though if you ask, laughingly we’d deny it.

We see Gordy sometimes, and his wife, june. Our grand-

children are friends. Hum Gordy’s old song

to make Gordy blush a fierce apricot hue

but it seems cruel, we’re all on blood

thinners now.

Comment form: