Here, in this darkened room of this old house,

I sit beside the fire. I hear again,

Within, the scutter where the mice carouse,

Without, the gutter dropping with the rain.

Opposite, are black shelves of wormy books,

To left, glazed cases, dusty with the same,

Behind, a wall, with rusty guns on hooks,

To right, the fire, that chokes one panting flame.

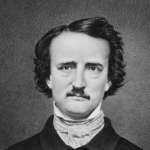

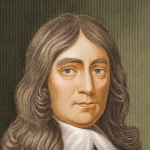

Over the mantel, black as funeral cloth,

A portrait hangs, a man, whose flesh the worm

Has mawed this hundred years, whose clothes the moth

A century since, has channelled to a term.

I cannot see his face : I only know

He stares at me, that man of long ago.

I light the candles in the long brass sticks,

I see him now, a pale-eyed, simpering man,

Framed in carved wood, wherein the death-watch ticks,

A most dead face : yet when the work began

That face, the pale puce coat, the simpering smile,

The hands that hold a book, the eyes that gaze,

Moved to the touch of mind a little while.

The painter sat in judgment on his ways :

The painter turned him to and from the light,

Talked about art, or bade him lift his head.

Judged the lips’ paleness and the temples’ white,

And now his work abides ; the man is dead.

But is he dead ? This dusty study drear

Creaks in its panels that the man is here.

Here, beyond doubt, he lived, in that old day.

“He was a Doctor here,” the student thought.

Here, when the puce was new, that now is grey,

That simpering man his daily practice wrought.

Here he let blood, prescribed the pill and drop,

The leech, the diet ; here his verdict given

Brought agonies of hoping to a stop,

Here his condemned confessioners were shriven.

What is that book he holds, the key, too dim

To read, to know ; some little book he wrote,

Forgotten now, but still the key to him.

He sacrificed his vision for his coat.

I see the man ; a simpering mask that hid

A seeing mind that simpering men forbid.

Those are his books no doubt, untoucht, undusted,

Unread, since last he left them on the shelves,

Octavo sermons that the fox has rusted,

Sides splitting off from brown decaying twelves.

This was his room, this darkness of old death,

This coffin-room with lights like embrasures,

The place is poisonous with him ; like a breath

On glass, he stains the spirit ; he endures.

Here is his name within the sermon book,

And verse, “When hungry Worms my Body eat” ;

He leans across my shoulder as I look,

He who is god or pasture to the wheat.

He who is Dead is still upon the soul

A check, an inhibition, a control.

I draw the bolts. I am alone within.

The moonlight through the coloured glass comes faint,

Mottling the passage wall like human skin,

Pale with the breathings left of withered paint.

But others walk the empty house with me,

There is no loneliness within these walls

No more than there is stillness in the sea

Or silence in the eternal waterfalls.

There in the room, to right, they sit at feast ;

The dropping grey-beard with the cold blue eye,

The lad, his son, that should have been a priest,

And he, the rake, who made his mother die.

And he, the gambling man, who staked the throw,

They look me through, they follow when I go.

They follow with still footing down the hall,

I know their souls, those fellow-tenants mine,

Their shadows dim those colours on the wall,

They point my every gesture with a sign.

That grey-beard cast his aged servant forth

After his forty years of service done,

The gambler supped up riches as the north

Sups with his death the glories of the sun.

The lad betrayed his trust ; the rake was he

Who broke two women’s hearts to ease his own :

They nudge each other as they look at me,

Shadows, all our, and yet as hard as stone.

And there, he comes, that simpering man, who sold

His mind for coat of puce and penny gold.

O ruinous house, within whose corridors

None but the wicked and the mad go free.

(On the dark stairs they wait, behind the doors

They crouch, they watch, or creep to follow me.)

Deep in old blood your ominous bricks are red,

Firm in old bones your walls’ foundations stand,

With dead men’s passions built upon the dead,

With broken hearts for lime and oaths for sand.

Terrible house, whose horror I have built,

Sin after sin, unseen, as sand that slips

Telling the time, till now the heaped guilt

Cries, and the planets circle to eclipse.

You only are the Daunter, you alone

Clutch, till I feel your ivy on the bone.

Comment form: