in memory of R.I.S.

1.

Would I know her anywhere, this child

who never knew you except in photographs?

She has your high clear polished forehead, but

“No, my sister has his dimple, the cleft

in his chin ...”

Tight curly hair (like yours)

drawn back, and your face, thinned, refined,

to a girl’s—you in a girl’s body, you

(thick, muscular, tempestuous)

newly slight, polite: you in a neat

print skirt, loose black blouse!

Now a seventeen-year-old classicist—

“Latin’s my favorite”—you translate

Catullus, write tidy sonnets, envy the sister

who remembers the dead father,

but (as you always did) adore your mother

and walk with your head thrown slightly back

as if the weight of thought were hard to bear.

I rock in my teacherly chair.

She’s shy, constrained.

“I don’t want to read my father’s poems,

they’re all in tatters in the closet,

they scare me.”

I tell her

I’m kind of a long-lost aunt, tell her

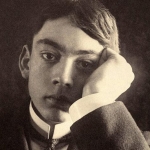

about the photo of you as (you said) “the young Shelley”—

about your huntsman’s bow, opera, baseball,

endless games of chess in the dorm parlor with you

boasting your prowess.

And she’s embarrassed,

you’re embarrassed, living in her blood,

to think you ever acted like that!

2.

When you were a man, a thirty-seven-year old,

long after our last fight, last kiss,

you OD’d on morphine

and disappeared into the blanks

that always framed your mind.

But she’s sent two poems and a thank-you note,

and her handwriting—yours—hasn’t changed.

“It meant a lot to me to talk about my dad,”

you scribbled with your new small fingers.

I want to believe this, want to believe

you’re really starting out again!

Do me a favor:

forget

Catullus, Horace, love and hate

and think, instead, of the epic

cell, the place where the chromosomes

are made and made for a moment perfect.

Translate those lines from Virgil

some of us once liked to chant,

the ones about beginning, about those who first

left Troy to seek the Italian shore.

Comment form: